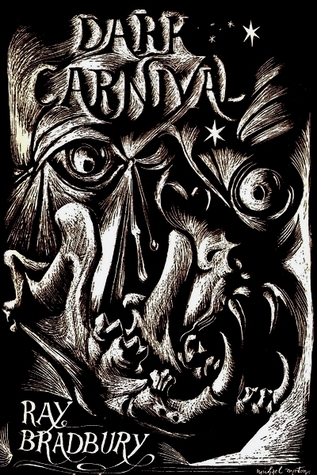

One of the tricks with writing horror, I think, is to not let the reader know that that’s what you’re doing. Allowing the reader to lose themselves in the writing may just be enough to blind their eyes to the terrors the writer is planning to unleash until those fiends bop the reader on the nose. That’s what happened to me when reading Bradbury’s The Emissary, originally published in Dark Carnival (1947). I’ll say here, that if you haven’t read it, then go and rectify that now (it is available for free online), and then return. Do promise to come back though.

When I was introduced to Bradbury, with the novel, Something Wicked This Way Comes, I found his frenetic style, his prose that seems to be an enthusiastic mish-mash of emotions and images, quite difficult to follow at first, but his lyricism has a magic to it that holds you to the story. Either that, or he’s just damn good fun! Fun; remember, the reader isn’t supposed to know they’re reading a horror story.

The Emissary is about Martin, a bed-ridden boy, his pet, Dog, and the “young, laughing, pretty school teacher”, Miss Chun Chang-cheon. The story fits into a horror subgenre and has childhood, loneliness, death as its themes. It’s a story about something that we all have some experience. It’s a story that makes us think, as all good horror and all good fiction does.

The skilful, very natural, way Bradbury narrates this story from the point of view of Martin produces powerful characterisation; we are there in that room with Martin, feeling what he feels, hearing what he hears. “Now, Martin heard dog returning through the warm afternoon sun, barking, running, barking again. Footsteps came following after dog. Somebody rang the downstairs bell, softly. Mom answered the door. Voices talked.”

Bradbury is adept at conveying the simplistic language and evolving thought processes of children which may reach the reader on some sub-conscious level and turn off the safety switches in our adult brain that prevent us from using our imagination too much, but more importantly, it immerses the reader into the main character’s world.

We have no description of the dog; even its name is Dog, reminding us that the pet is simply there to bring the outside world to Martin. “Over a tall hill, leaving footprints in the tall hills of leaves, down to where the kids ran shouting on bikes and roller skates in the Park, […] And down into the town where rain had fallen dark, earlier; and mud was under car wheels, down between the feet of week-end shoppers. […] And wherever Dog went, then Martin could go too; because Dog would always tell him by the touch, feel, the wet, dry, or weather-smell of his coat.”

By Martin’s act of putting a note around Dog’s neck, on which is written, “MY NAME IS DOG. WILL YOU VISIT MY OWNER, IS SICK? PLEASE FOLLOW ME!”, Bradbury conveys Martin’s desperation and loneliness, and thus endearing Martin to the reader.

The description of Miss Chun is brief but succinct: “way she smiled, […] her bright eyes, her soft chestnut hair, her quick walk, her nice stories about castles and people.” She is the only character that is described, and it happens in two places. It is the lack of description of the other characters (even the other visitors are only named and referenced by their occupation), that gives Miss Chun much more weight and importance.

His kind-hearted mum, the other character in the book, is significantly less detailed than the school-teacher, and is relegated to dialogue. As well as highlighting the importance of Miss Chun, this also shows a boy’s possible view of his mum, as a person that is ‘just there’, ‘just mum’.

If you haven’t read this story (what are you still doing here? I thought you were skipping over to it) then I’m not going to spoil your enjoyment by telling you the end. If you have read it, then you may agree with what I’m about to say. The conclusion is utterly brilliant in its simplicity and, for me a reader who was lost in Martin’s world, I never saw it coming. It was this that caused a chill to run down my spine when I reached the last sentence.